Reproducibility in the Spotlight:

Psychology is still reeling from the results of a massive study of

reproducibility

which found that less than half of statistically significant findings recently

published in the top psychology journals remain significant when independently

reproduced. If this is new to you, Jesse Singal wrote a great summary about it here.

Biology is not exactly doing that much better. Ioannidis first highlighted

shoddy research practices in biology with his aptly named paper

Why Most Published Research Findings Are False.

The latest entry in this saga is discussed in this

excellent article from Nature. In papers that rely on animal models, the

results are too fragile and unreliable to be used as a basis for further

research because the statistical design of the experiments is often

critically flawed. This is unfortunately not a huge surprise: scientists

at Bayer had already warned that published data had become progressively less reliable as

basis for drug research.

In a previous editorial,

Malcolm Macleod points out that:

The most reliable animal studies are those that: use randomization to eliminate

systematic differences between treatment groups; induce the condition under

investigation without knowledge of whether or not the animal will get the drug of

interest; and assess the outcome in a blinded fashion. Studies that do not

report these measures are much more likely to overstate the efficacy of

interventions. Unfortunately, at best one in three publications follows

these basic protections against bias. This suggests that authors,

reviewers and editors accord them little importance.

For those that aren't familiar with experimental design - these aren't hyper

advanced techniques. Those are all things which are taught in a 1st year graduate

experimental design course and that every senior scientist should be very

familiar with.

Animal Models In Science:

What makes this particularly frustrating is that in this case, the scientists

aren't just wasting public money, but they are killing loads of animals for

absolutely no public good. Until computational models massively improve,

research with animal models is absolutely necessary, especially in the later

stages, when we wish to validate promising drug targets or test drug safety.

In theory, the use of animal models in research in the US is

strictly regulated

by the NIH. In practice, while charges of animal cruelty are taken seriously,

poor protocol design leading to a waste of model animals is very rarely

sanctioned.

You Always Get What You Measure:

Why do really smart scientists make such stupid mistakes?

-

Arrogance: Some oldschool PIs are so confident in their own theories that they see

statistics not as a critical way to evaluate their data, but as a simple

threshold (p < 0.05) they gotta cross to be able to publish. This is thankfully

not very common, but if you go to any bioinformatics conference and talk over drinks

to some of the junior people there, you'll hear all sorts of horror stories about

being the only bioinformatician in a group and having to somehow come up with a

statistical test that gives p<0.05.

-

Misaligned Incentives: This is unfortunately very common. The currency of

scientific careers are publications in high impact journals, and the easiest way

to publish in those journals is to produce splashy results. Unfortunately,

results are the one thing that scientists have no actual control over - if you

execute a well designed experiment to test a reasonable hypothesis, the

actual outcome is up to the Universe. By dis-proportionally rewarding splashy

results, we punish the scientists that actually do research properly, since they

will have a much lower fraction of positive results.

The irony that Nature, one of the most prestigious scientific journals in the world,

acknowledges that scientists push splashy but unreliable findings (like say,

these)

instead of solid but boring ones is not lost on me. It reminds me of the time

a Facebook executive complained that the Internet was drowning in shitty click-baity articles, when the

product he was responsible for was the main driver of that behaviour.

It's important to add that the quest for high impact publications is not

just motivated by a selfish desire for success. Postdocs are facing a very

difficult job market and are desperate to have a high impact paper before

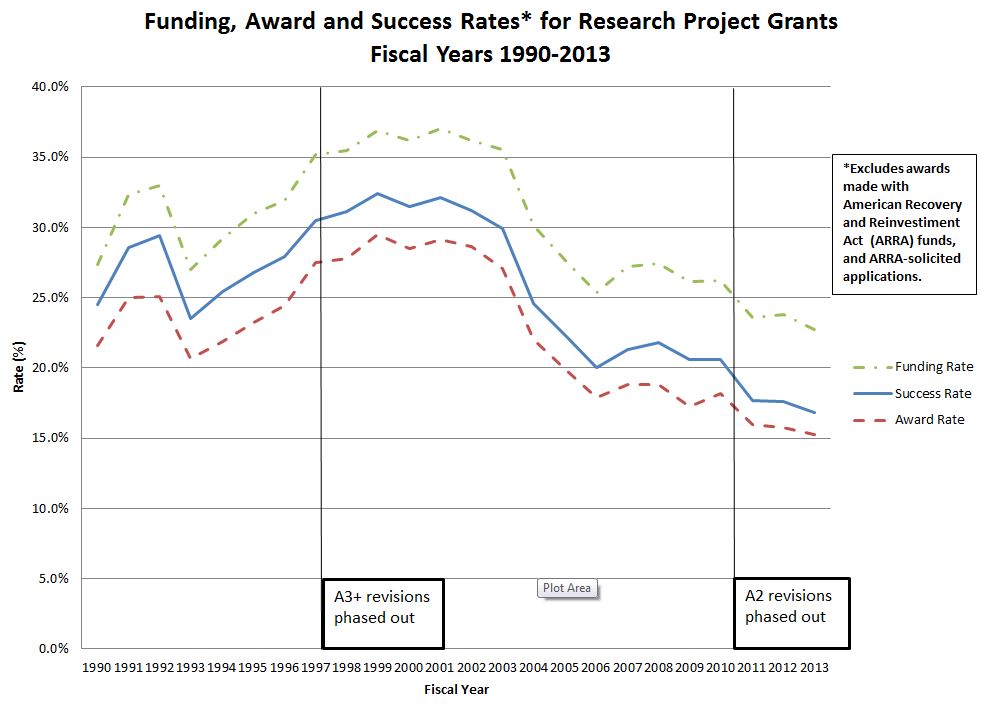

applying for tenure track positions. PIs are under an immense amount of

pressure

by their institutions to obtain grants, and it's getting harder and harder.

Further, missing grants doesn't just hurt the career of the PI. Very few people

in science have the luxury of fixed positions - even lab technicians and staff

scientists are often funded by grants, and not getting a grant renewed can mean

having to fire people people you've worked with for many years.